The Rise

It could be the opening shot of a Hollywood movie. At the beginning of The Rise a man is looking out over the South Axis which is under construction. Standing in front of a window with his back to us, he stares at the area which the city of Amsterdam dreams will become a new centre that will leave the old, canal ridden and congested space ultimately to tourists. We cannot read his gaze, but his stance is instantly reminiscent of the classic cinematic depiction of power and unbridled ambition. The setting aptly sums up the South Axis plans: its showy buildings by top architects such as Viñoly and Ito, and its complete accessibility by motorway, train station and airport, bring together an almost mythic concentration of will and capital in the area that is stretched out at his feet, while the two large vases that flank the window testify that culture is also high on the agenda.

Suddenly we are in another spot. Someone is ascending the staircase that is cut into the façade of one of the office towers. For the rest of the film we follow this man in his endless upwards trek. A new stretch to be climbed awaits him at each corner of the building. The structure stretches dizzyingly above him, and although he has already risen to a great height, he doesn’t appear to get any closer to the top. Time goes by, he spends the night on a projecting roof somewhere halfway up the building, another day passes, but he does not seem to get anywhere. From time to time he has a brief encounter with the fleeting shadow of a child, and gets involved in a struggle with someone who appears to be his twin. A motorway can be seen in the background, and now and then an aeroplane glides noiselessly past in the sky. But he is isolated in his endless journey to the top.

It is not only the music that is responsible for the unmistakable sense of threat that hangs over the film. What the threat is, however, is not immediately clear. When one is dealing with tall buildings, endless stairs and the dizzying drops that ensue, doppelgängers and mistaken identities, one immediately thinks of Hitchcock’s Vertigo. But in that film the main character’s acrophobia is an assignable cause of his traumatic experience, and his falling for the lookalike is driven by desire. However, the anxiety of this stair climber has no clear cause, it is not even clear what motivates his climb. He seems driven by an exigency without purpose, an ambition without desire. He climbs onwards in an almost perfunctory manner, and his anxiety appears to be prompted by the top rather than the abyss below. He is driven on by the fear of never achieving the heights, but perhaps he is filled with anxiety over the void that awaits him there. In his exhausting trek he is the perfect example of the ideal office worker, a subservient member of the expensive-suit proletariat for whom the way to the top is the only option.

Somewhere on his way he enters an office, but it is empty. The man doesn’t seem to know what he is looking for, and climbs on further. But we know now that there is nothing going on in this tower, the exterior of which radiates such dynamism and authority. We know that all this haughty steel, glass and concrete conceals only an emptiness in its heart, and that the tower’s own upward drive also stems from a blind desire to reach the top. Thus, as in most of the films by Fischer and el Sani, architecture plays a central role. However, while most of the films deal with the emptiness of buildings which were once charged with ideological or utopian significance, these office towers have not lost their content; their ideal is found exclusively in their exterior. Their main asset is their outward uniqueness, and they regard their height as their greatest virtue. And just as the man no longer has any sense of why he continues to climb the stairs, the office towers of the South Axis have no idea why they are trying to storm the heavens. They press upwards out of blind ambition and compete with one another out of hubris.

In what might be the final shot, the man looks over towards the tower opposite him, and there he sees his carbon copy standing in front of the window. The twin he struggled with on the stairs seems suddenly to have defeated him to the top. But what is involved here is not the theme of the doppelgänger or the shadow, as this has undermined faith in the human subject since Romanticism; once again, it is about architecture. The uniformity which once was the hallmark of a well-functioning office building, the seriality which guaranteed the efficiency of mass production, has now become a bogey. To the extent that globalisation succeeds better in reducing everything to sameness, emphasis on exceptionality or specificity increasingly becomes a necessity, even if it is just to maintain a suggestion of the concentration and concretion of power. For a long time now the world-encompassing web of cash flows has no longer had booms and busts; everywhere, at the same moment, it can be present or absent in the same way. But, in striving for the top, the building benefits from acting as if it is still intent on some purpose. In doing so it offers a sense of purpose to the workers who, in their eternal trudge upwards, keep the money-flow treadmill in motion. At the moment their eyes meet, both men realise that the way to the top is also the way down. However, because the film is a loop, they are locked in an eternal struggle for the top without a chance of escape.

There is more involved here than simply a feint that the threat is real. The office towers that confront one another in the South Axis stand for quality and culture. But at the moment when they reflect each other, they see the vacuum of their hollow pride. As stiff soldiers of capitalism, they lose all their lustre and heroism; only with difficulty can they carry out their commission. They are twins in the depths of their empty souls.

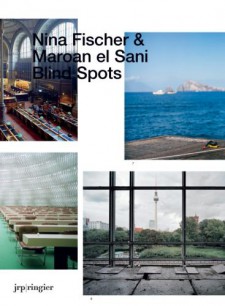

Published in: Nina Fischer & Maroan el Sani – Blind Spots, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, Amsterdam 2008.